Awestruck by the Thought Spinner (aka The Electrum Archive Rocks!)

#002 - Make settings easy to grasp at the table

RPG books are a form of art. Period.

I could end my blog post here and still add value to the world. But let’s go deeper. Creating an RPG book requires storytelling, evocative descriptions, stunning artwork, clever mechanics, gameable content, and tools that enhance play. These elements must work seamlessly to create an immersive experience. As this newsletter grows, I want to explore the many facets of game design. Where to begin? With what’s closest to my heart: settings and lore (and why The Electrum Archive presents them so damn well).

What Parts of a RPG Get You Excited?

For a long time, I thought the answer was obvious—settings! But I’ve come to realize that excitement for RPGs comes from many sources. Some love character options, tailoring their PCs for any world. Others are drawn to mechanics, preferring solid rules and procedures over built-in lore. And my sister, Nina, will have a book’s art and layout dissected before she’s even read a single word. People connect with different aspects of RPGs, and power to them all!

Recently, Uncanny Ramblings wrote a comprehensive, but not exhaustive list of OSR settings. A game’s lore and vibe are what ignite my imagination. If a setting is rich, I mentally dive into its world, exploring its secrets, envisioning scenes and stories. If you can set my thoughts spinning and want me to bring your world to life at the table, you’ve won me over.

But if a setting is too bland, indistinct, or overly derivative, that spark fades, and I might lose interest. Personal preference plays a role, but I believe strong writing and worldbuilding are key to a memorable RPG. That said, a GM trying to become the next Tolkien doesn’t always make for the most fun at the table (as Dungeon Dorks Podcast explains).

How developed can a setting be?

Fully Developed Settings: Settings can be developed to incredible depth—sometimes to an overwhelming degree. Dolmenwood by Gavin Normann (Necrotic Gnome), inspired by British medieval folklore, comes to mind. This one’s high on my anticipation list. Ben Milton even called it the “richest DnD setting I’ve ever seen”. Or the upcoming setting book for Pirate Borg, The Dark Carribean by Luke Stratton (Limithron), with previews available on their Patreon.

I love how these expansive settings, spanning hundreds of pages, offer deep sandboxes where a gaming group could explore for years. Their rich backgrounds immediately draw me in, and as these two examples are designed for usability—perfect! When I prepare a game from such a hefty tome, I usually have a medium or long-term campaign in mind. However, as much as I dream of endless exploration, the sheer scale can also be daunting. Even with random generators for improvisation, I spend significant time understanding and absorbing the setting. Not everyone has the time or desire for that level of prep.

Procedurally Generated or Implied Settings: Of course, there are other worldbuilding approaches, too. Think Vaults of Vaarn by Leo Hunt, a science fantasy world in a vast blue desert. While the setting is very specific and unique, not many locations or truths have been spelled out. Instead, the game offers a plethora of highly creative tables and generators to procedurally create the world bit by bit at the table.

The same could probably be said about Cairn 2e by Yochai Gal, which only implies a fantasy forest setting, but leaves it to the group to use the provided tools to flesh it out. All the famous works of Chris McDowall fall into the same category.

I have to admit that it took longer for those games to click for me. When I started playing TTRPGs, every game I knew came with hundreds of pages of fictional history. At first, that felt essential. But more often than not, all that lore proved to be a burden at my table, as I was busy memorizing things and my players couldn’t always grasp the whole concept. They weren’t there for a lesson in fictional history—but for an adventure!

Either richly developed or generated: Ultimately, it’s about making the cornerstones of the setting easy for players to understand in advance, giving them meaningful ways to interact with the world, and then letting the setting gradually unfold in the game. In any case, players will only remember what they have experienced and what has become relevant to them.

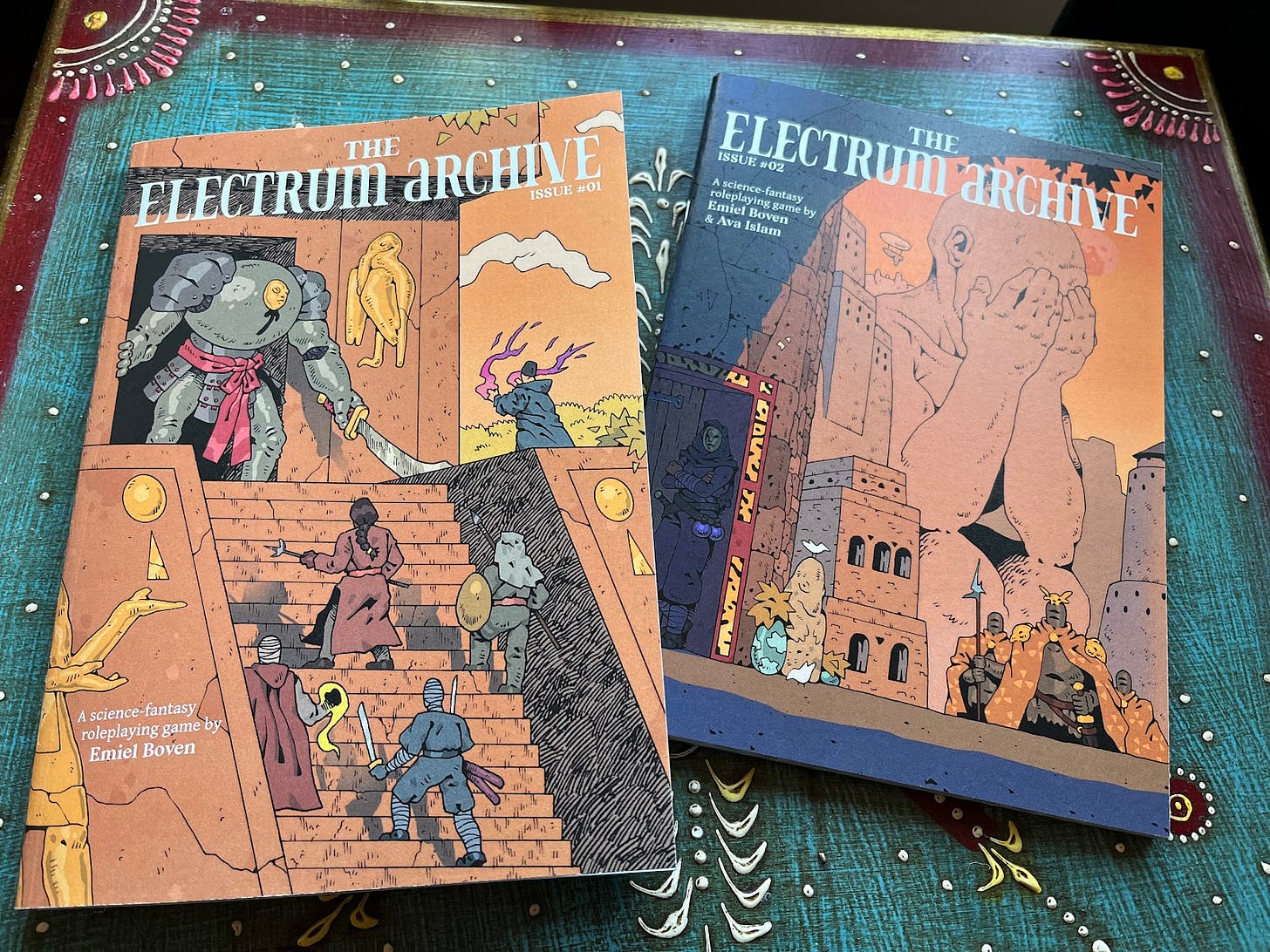

Recently, though, I found a game that somehow threads the needle between a deeply developed and an implied setting almost perfectly: The Electrum Archive by Emiel Boven and Ava Islam (Cult of the Lizard King).

Describe Your Setting On One Page

The Electrum Archive (TEA) is a science-fantasy RPG set in Orn, a world where ancient starfaring Elders brought humanity before mysteriously vanishing. Their ruins, ink-powered technology, and lost knowledge form the backdrop for a land of scavengers, warlocks, and warring factions. Here, gold and silver are worthless—Elder Ink, a magical substance left behind by the Elders, is the true currency, granting power and access to the Realm Beyond, where spirits dwell. Orn is a world of crumbling trade empires, spirit-possessed artifacts, and fungal horrors. Players carve their own destinies through adventure, exploration, intrigue, and survival.

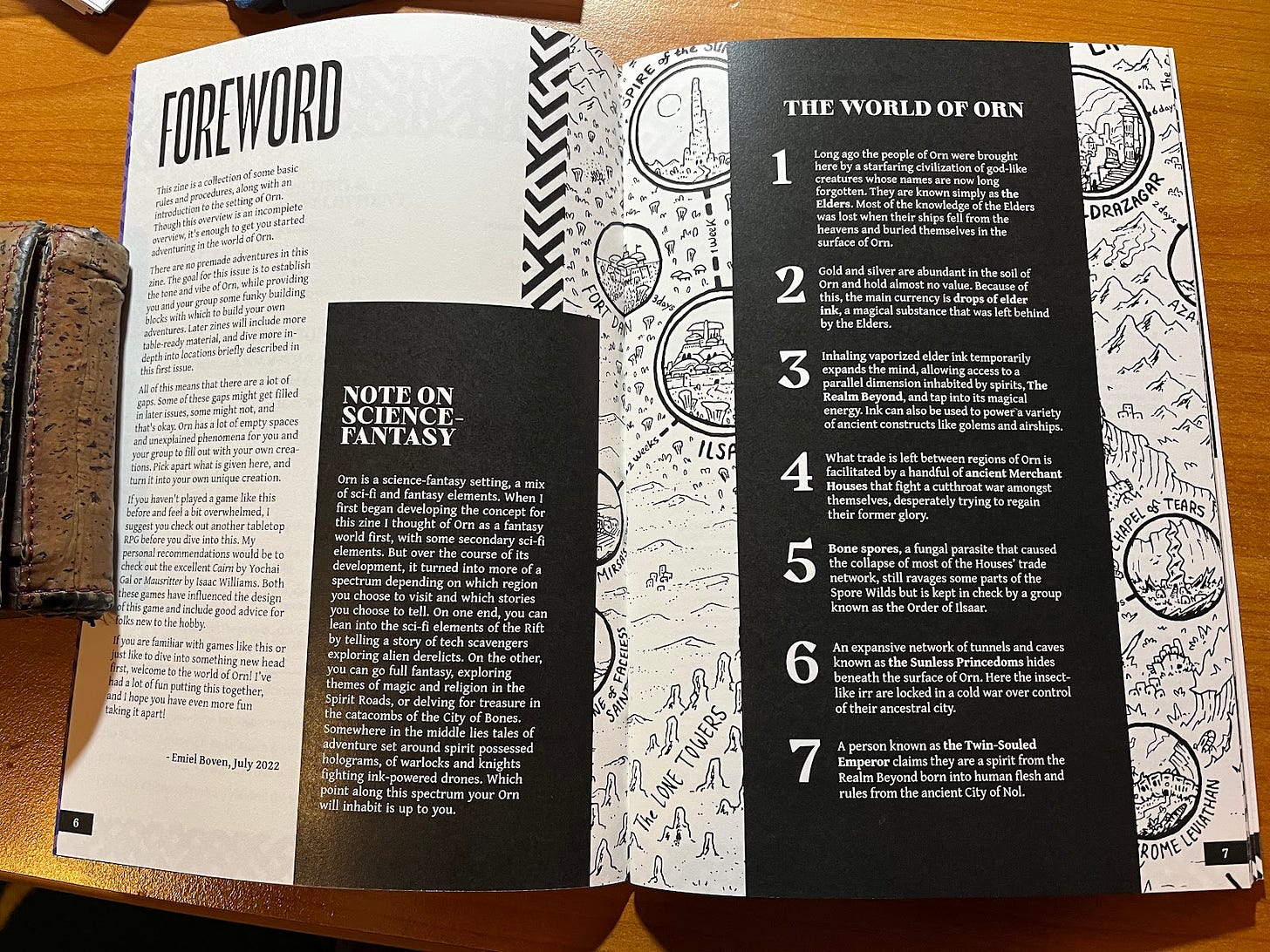

Issue #01 of TEA is “a collection of some basic rules and procedures, along with an introduction to the setting of Orn”, as the foreword tells us. This is a 70-page A5 zine. What I continually found astounding is just how much information is conveyed with so little text. The writing is extremely evocative, portraying a believable, vivid, and extremely interesting world in a relatively small amount of space. This begins with the fact that the seven pillars of the setting are already set out explicitly in the first content-filled spread.

TEA also impresses with how well it can handle its space. Every key topic is allocated exactly one double-page spread—e.g. factions, the world of Orn, a timeline of major events. However, these are never cluttered with text. Each section is clear, concise, and supported by artwork.

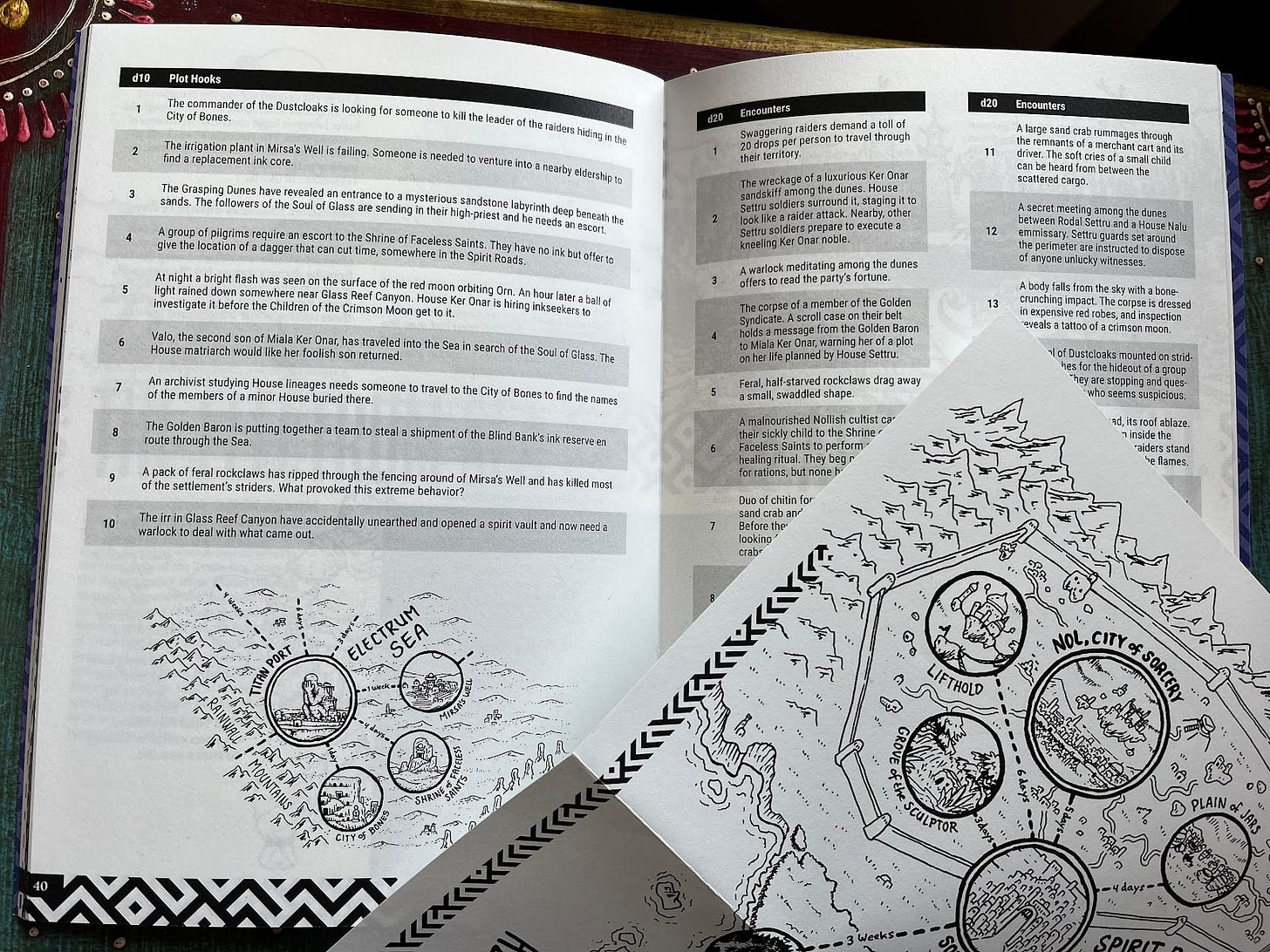

Scattered throughout, the authors weave evocative lore snippets that fuel the imagination. The tables below on plot hooks and encounters in the region called Electrum Sea, for example, are deliberately kept very specific. They flesh out the world while providing immediately usable content.

This allows the factions in particular, which were previously only presented in short 80-word paragraphs, to be further elaborated. Both the GM and the players get to know them, their behavior, and their relationships through very concrete situations. As a result, these tables will perhaps not encourage endless replay, but will likely provide very practical support for most campaigns. This principle is also repeatedly applied in the zines beyond the factions.

Final Thoughts

The setting is deep and creative, easy to explain, paints a vivid world, and can actually be experienced by players through very concrete, exemplary scenes and encounters. It strikes a near-perfect balance between predefined lore and emergent storytelling.

TEA has amazed me in more than one way, which I will discuss again in a later blog post. There’s currently the first TEA jam happening on itch. If I had more time, I’d be diving in already. By the way, many tables and generators from the aforementioned Vaults of Vaarn fit perfectly into the world TEA (and vice versa).

If you love OSR, subscribe to our newsletter, follow along, and let’s dive into this world together.

“From pebble to monolith—your journey matters. The Golems have spoken.”

Alexander from Golem Productions

TEA is such a good setting! I just finished my first read through of the first zine. I would definitely consider running it for my group.

I hope later zines add and flesh out some elder tech. That was the only thing I really found lacking that I would need to run. If I ran it, I would just reskin OSR items from other books. That should work well enough with a spattering of homebrew items. With the simple progression system, my players would be itching for something else for their characters.

Great write-up!