Do TTRPGs Have a Grimdark Problem?

#014 - Grimdark Overload vs. “Mature” Themes. And why I don't need another (grim)dark fantasy setting.

These days, tabletop RPG adventures seem saturated with grimdark elements – bleak worlds, brutal violence, and nihilistic tones. Many creators equate “darker” content with being more mature or serious. But is darkness really necessary to tackle adult themes?

As blogger Augury Ignored notes, when games lean into “overwhelming bleakness” with an “overabundance of openly anti-positive themes”, it often “cheapens it and robs it of its impact”, making the experience exhausting rather than engaging. Grimdark done poorly risks becoming try-hard edginess that leaves players apathetic instead of immersed.

As I am myself publishing and running content for Pirate Borg, and enjoy running games like ALIEN RPG or Mothership, it is time to address this topic that has been on my mind for a long time.

Grimdark Overload vs. “Mature” Themes

To be completely honest, I’m getting a little tired of the many new “(grim)dark” settings and games that are being released one after another. Some of them really repel me. I want to have fun with family and friends, not act out fantasies of violence and power or watch others do so. And some games boringly just appear to me as being “dark” as an end in itself.

But then why are there still “dark” games that fascinate me and entertain me well? I’m afraid I won’t be able to answer this question conclusively in this article, but perhaps it will serve as a starting point for a longer train of thought.

So, let's start with the assumption of darker settings being more mature. Importantly, “mature” doesn’t have to mean cruel or joyless. I can’t stand cruelty. You can for sure explore serious topics without bathing every scene in blood and despair. In fact, too much relentless darkness can be quite un-fun. Players may grow numb or disconnected if nothing they do matters against a hopeless backdrop.

The fun in RPGs, even horror or dark fantasy, often comes from contrast and agency – the ability to overcome challenges, however grim, and shine a light in the darkness.

In other words, darkness should exist to make the players’ struggles meaningful, not to render them futile.

Is it useful?

So why do grim settings persist? When I interviewed Gavriel Quiroga, he argued that confronting nightmare scenarios in games can be cathartic or thought-provoking. By role-playing through worst-case scenarios, players safely explore how they’d react to real-world challenges, whether that’s surviving a natural disaster or resisting a dystopian regime.

An there seem to be some “practical” side effects as well: Bleak worlds make consequences legible. When light, air, ammo, or reputation are scarce, choices feel meaningful. And, yes, heavy-metal art telegraphs tone in a single spread—it sells a vibe fast.

But I have the feeling that grimdark fatigue is real. Not every table wants Game of Thrones with dice. RPGs are also imaginative escapism, and even serious campaigns need room for hope, heroism, or the odd goblin parley. A dash of levity doesn’t make play childish—it makes the dark moments land.

The OSR Ethos: Heroes, Murder-Hobos, and Morality

In old-school play, PCs have long skewed closer to resourceful rogues than sworn paladins as opportunists chasing coin in hostile places. Early OSR blogging often embraced the idea that D&D structurally enables a detached, amoral stance: choices are treated instrumentally, because the game rewards tactical problem-solving over scripted morality.

That doesn’t mean OSR equals constant murder. In fact, classic procedures push players away from fair fights and toward talking, tricking, mapping, and clever workarounds: reaction rolls to parley, morale to end fights early, 10-minute turns to pace risk, and encumbrance to make logistics matter. Exploration and social play are pillars of the OSR, not afterthoughts.

The “murder-hobo” label became community shorthand for groups who roam, loot, and leave chaos behind, but it’s a caricature of a broader style. Well-run OSR tables prize player skill—caution, ingenuity, negotiation—over linear combat grinds.

Lately, there’s also a counter-swing toward earnest heroism. After years of ironic grimness, some voices explicitly ask: what if we play unapologetic “good guys”? That impulse sits comfortably alongside the procedural toolkit; nothing about reaction rolls or turn clocks forbids virtue. It simply means agency first: players decide who they are—mercenaries, explorers, or would-be saints—and the world reacts.

Weirdhope as Counter to Grimdark

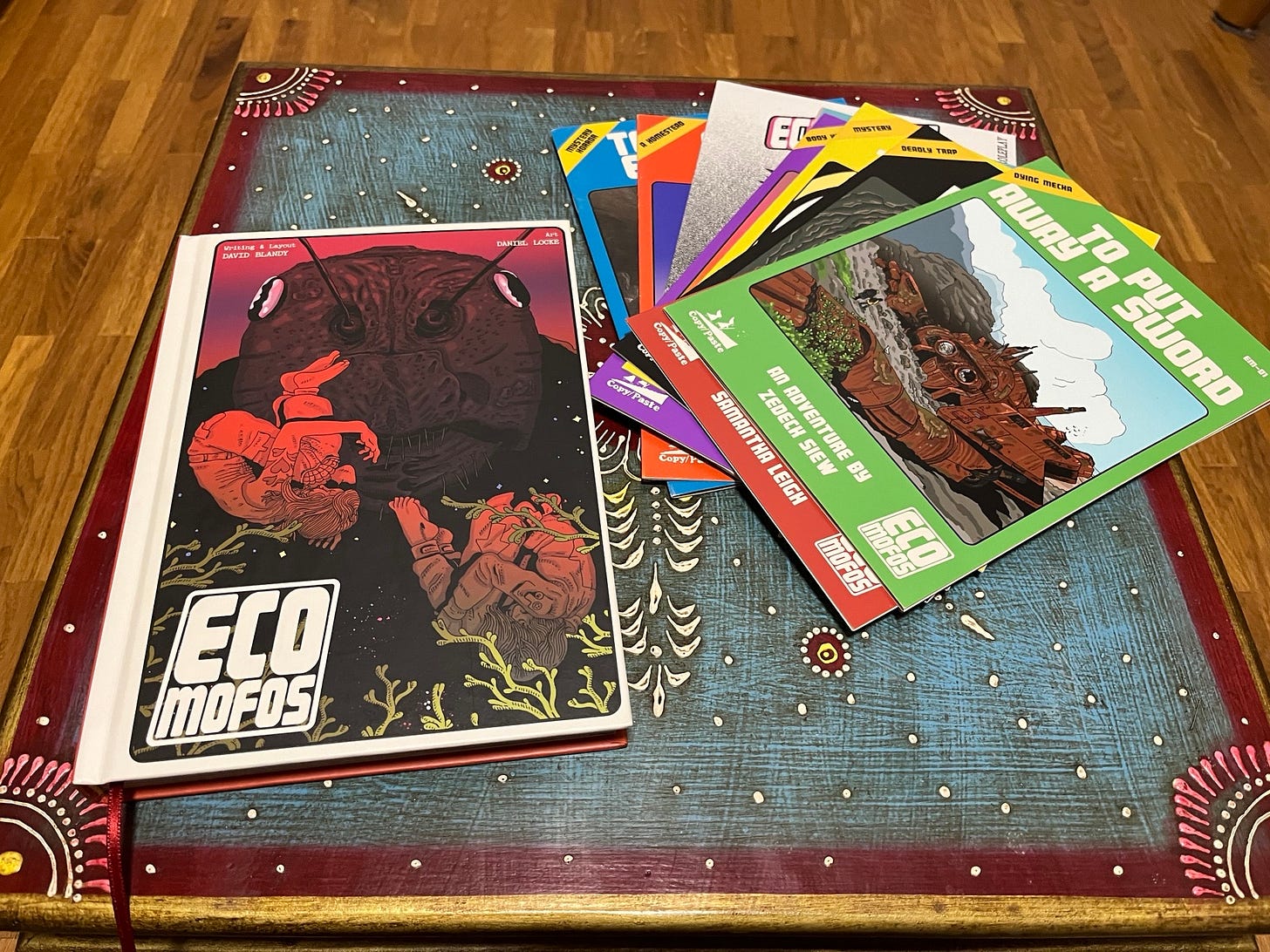

If grimdark has dominated the past decade of RPG design, a new wave of creators are experimenting with its opposite: weirdhope. The term was popularized by indie designer David Blandy, who openly tags his games as “Weirdhope not Grimdark.” His 2023 release Eco Mofos!! (with artist Daniel Locke) is a perfect case study: a post-apocalyptic world that looks like Mad Max but plays like Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. There are mutant critters, toxic ruins, and plenty of danger—but instead of despair, the game is about “stories of discovery and resistance.” Its punk energy comes not from cruelty, but from the rebellious act of choosing hope in spite of collapse.

Weirdhope games often cast players not as mighty chosen ones but as agents of possibility. In Eco Mofos!!, you play a scrappy band of misfits banding together to build a future. The past is a hazy legend; the future still unwritten. In Locke’s words, the concept of weird hope is central: even in a poisoned world, optimism itself is punk. That ethos is reinforced by its vibe list: not just dystopian comics like 2000AD, but also Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, Butler’s Parable of the Sower, and Star Wars: A New Hope.

Eco Mofos!!: Punk Survivors, Not Murder-Hobos

Eco Mofos!! deserves a closer look because it demonstrates how OSR-style play can be reframed around cooperation and renewal. Players form a crew of wasteland survivors—DIY scavengers closer to Tank Girl than Tolkien elves—who care less about treasure and more about carving out a safe place to live.

Mechanically, it’s rules-lite, based on Into the Odd/Cairn. Character creation uses lifepaths, and PCs carry Burdens—personal traumas that can only be resolved through play. There’s a giant d666 loot table, procedural adventure generators, and deadly hazards (characters can even die during character generation—a very old-school touch). Yet the ethical compass points differently: violence is an option, but not the goal. The emphasis is on exploration, creativity, and building something new in the ruins.

For OSR fans, the game proves you can keep the danger, randomness, and DIY ethos while steering away from nihilism. Survival is only the starting line. What matters is what you build after. In that sense, it’s one of the clearest statements yet of weirdhope: messy, punk, and defiantly optimistic.

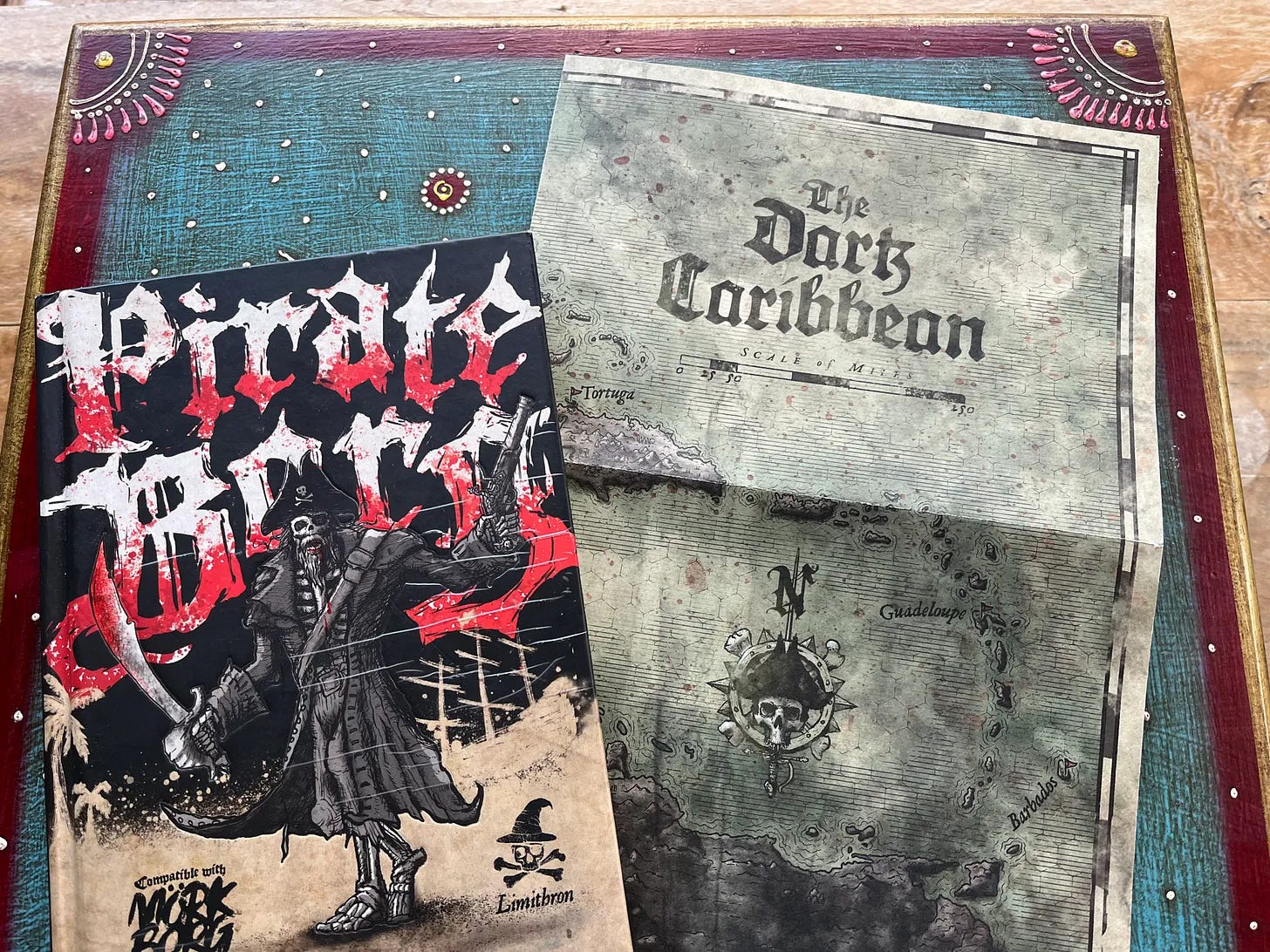

Pirate Borg: High Seas Grimdark (with a Conscience)

Pirate Borg is, in many ways, grimdark turned up to eleven. A spinoff of the doom-metal Mörk Borg, it swaps out plague-ridden Europe for a “Dark Caribbean” where ghost ships sail under storm-choked skies and the apocalypse looms with every tide. The tone is all skulls, blood, and doom—yet also exaggerated enough that it often loops back into gallows humor. Its Carousing table, for example, revels in drunken misadventures, and the magical drug ASH tempts players with power before turning them into zombies. It’s over the top, and it’s funny in a morbid way.

On the surface, that sounds like classic grimdark. And yet, what struck me most is how aware Pirate Borg is about its tone. Creator Luke Stratton makes this point crystal clear:

“Please remember… PIRATE BORG is a game about grog-swilling pirates, undead galleons, arcane treasures found in ancient temples, and high seas adventure. It’s not a game about slavery, sexual violence, genocide, or any of hundreds of other absolutely abhorrent real parts of our history. Please treat these topics with the respect they deserve, or leave them out of the game altogether and go hunt some skeletons.”

That statement impressed me. It shows Pirate Borg isn’t careless. It carves out a space for over-the-top fun without indulging in cruelty. The game makes room for everyone to jump aboard, roll a doomed buccaneer, and dive straight into chaos without brushing against themes that would alienate or harm.

Why Ravaged by Storms Builds on This

A good example of how OSR values can live inside a grimdark chassis is our current project, Ravaged by Storms. We designed it for Pirate Borg not as a linear dungeon crawl but as a mythic sandbox, to prove that even the most brutal systems can carry long-form exploration and emergent consequences. Many Borg hacks lean into linear hack-and-slash, but Pirate Borg’s Dark Caribbean begs for something more. We wanted to show that you can have the brutal fun of Pirate Borg and the longevity of a true OSR campaign.

For me, Ravaged by Storms became a chance to test this balance firsthand. Built for Pirate Borg, it embraces the game’s skulls-and-thunder vibe but frames it as a mythic sandbox rather than a one-shot brawl. The Coatl, storms, and factions all shift independently of the players, so the world evolves whether characters survive or not. That’s grim, but not empty—and it’s exactly the kind of meaningful darkness I’ve argued for.

In that sense, Ravaged by Storms is my answer to grimdark fatigue: proof that you can embrace the wild energy of Pirate Borg while still offering the kind of exploration, consequence, and possibility that OSR play thrives on. The skulls and storms are there, but so is the space for players to carve meaning out of the chaos.

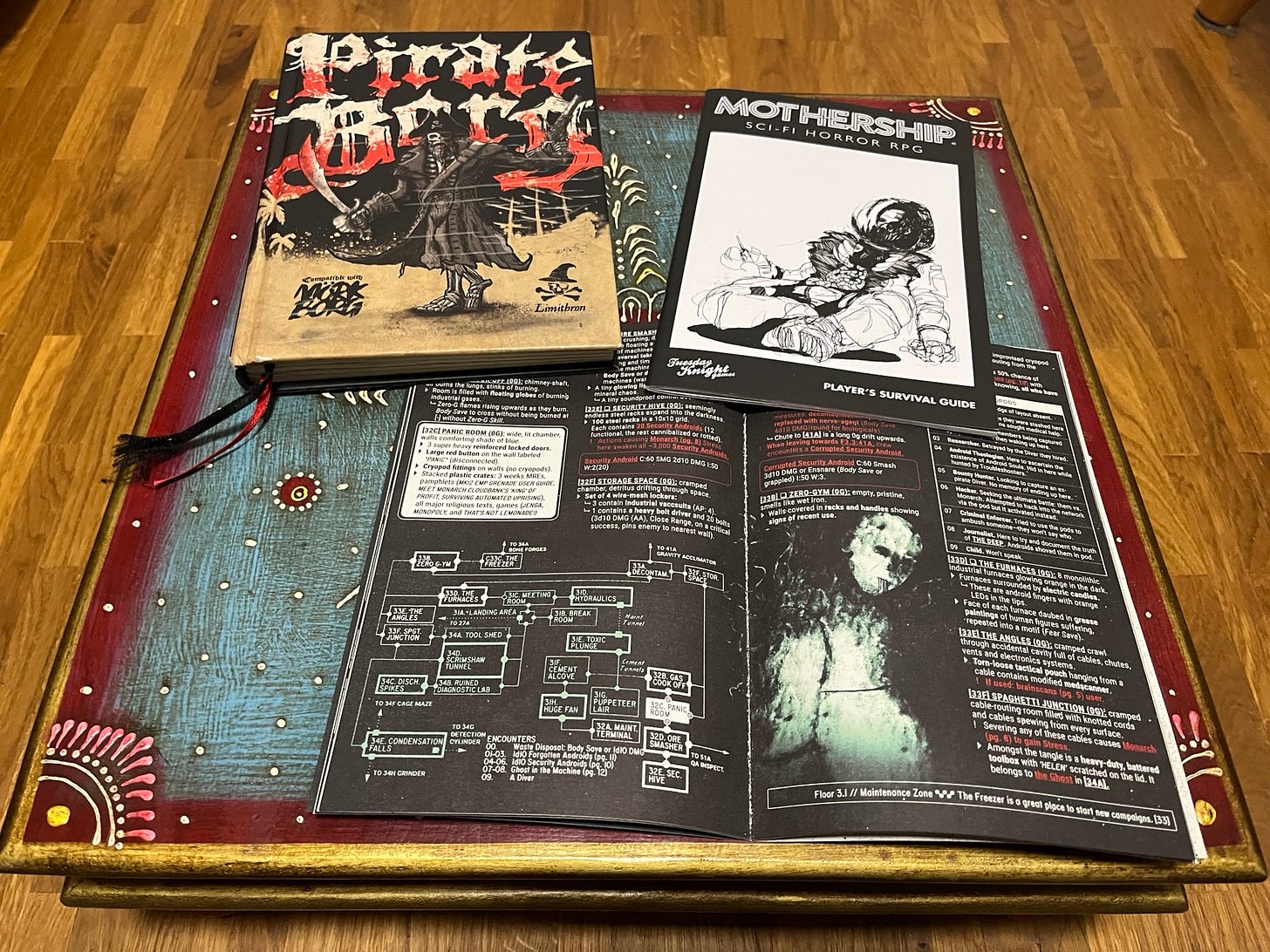

Pirate Borg vs. Mothership: Two Faces of Darkness

Pirate Borg and Mothership both lean into dark aesthetics, but they channel that darkness in very different ways.

Pirate Borg is grimdark with swagger: it invites players to revel in chaos—but, as Luke Stratton’s quote makes clear, it does so responsibly, cutting out real-world horrors like slavery or sexual violence. The experience is immediate, bloody, and often darkly comedic. The fun comes from style, speed, and the thrill of playing doomed rogues in a heavy metal nightmare.

Mothership, by contrast, is earnest survival horror. You play working-class spacers caught in terrifying situations. Its Panic Engine ensures the stress ratchets up as dangers mount, and the victories are measured in survival, not treasure. Ethically, it’s less about cruelty and more about realism: do you quarantine your infected crewmate, or risk bringing them aboard? Mothership doesn’t wink at the audience the way Pirate Borg does; its horror comes from immersion in a cold, uncaring universe.

Both games demonstrate the range of what “dark” play can mean. Pirate Borg shows that grimdark can be fun when it’s stylish, absurd, and conscious of boundaries. Mothership proves that darkness can be powerful when it’s grounded in tension and consequence, not just gore.

Neither offers traditional heroism—but both give players the agency to navigate danger on their own terms.

Finding the Fun Beyond Grimdark

So, do TTRPGs have a “grimdark problem”? In some ways, yes. When handled with creativity, even violent games can be stylish. Pirate Borg proves this: it’s bloody and chaotic, yet also self-aware and careful about boundaries. The problem arises when bleakness becomes empty misery, leaving players with no agency and no reason to care.

The best dark games give players meaningful choices—to save someone, to outsmart danger, to choose mercy over murder. In those moments, the surrounding darkness makes their actions shine brighter. A bad grimdark game, by contrast, traps players in futility.

But here’s the thing: I don’t need another grimdark fantasy setting. We have plenty already. What excites me are games that offer a twist—something beyond endless blood and despair. In any case, however, I reject games that are unimaginatively bleak, senselessly glorify violence, or demand that I perform atrocities. Personally, I’m not sitting down to revel in imaginative gore. I'm there to have an entertaining game night, whether the themes are serious or silly.

The real takeaway is that tone matters. Dark or hopeful, RPGs work best when they give players purpose and room to act. Sometimes meaning comes from facing the shadows—and sometimes from lighting a candle against them.

How do you feel about the “Grimdark”?

Which “dark” games do you like to play, and which ones aren’t your cup of tea?

We would love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

Just One Week Left on Kickstarter! - 3 Adventures, 15 Stretch Goals, >1000% funded!

“From pebble to monolith—your journey matters. The Golems have spoken.”

Alexander from Golem Productions

I think that the real problem is not grimdark itself but HOW people use it. A party of toxic players (and I've known many - too many, actually) can destroy even the most cheerful setting. And this kind of players (and GMs), I think, don't really care about one of the most fundamental elements of a TTRPG: a meaningful story.

Let me explain myself: there's no Peter Pan without Hook.

So, to be meaningful, even the bleakest grimdark setting can be awesome as long as it's counterbalanced by the perspective and the possibility of hope and kindness. Even WARPED hope and kindness will do, as long as they maintain a narrative relevance.

And I'm not referring only to the grand scheme of salvation (like Benjamin Decker insightfully stated is the case in LOTR): even small acts can counteract grimness.

In a short story I wrote, an old battered goon in love with a prostitute ends up in a terrible situation, only to be saved by an old mangy dog. The setting is grim, the characters are lowlifers and outcasts, the main stage of the story is a brothel and then a vast, ancient burial ground. The violence depicted is quite brutal, but a simple act of kindness acts as a great force that can reverse (almost) every tide.

So, again, settings are not the real issue, nor a problem.

Dominance and power fantasies and crass ignorance of the basic principles of what drives narrative are the real culprits. Even the most horrible acts and scenarios can serve a good narrative, as long as there's the will to build a great story.

There's nothing wrong with using dark, heavy elements and actions - even settings - as long as you serve a good narrative. But violence for violence's sake only goes so far. It's simply BORING. And boredom is the real fun-killer.

By the way, thank you for bringing up this conversation, I think I'll write something about this topic

I’m over bleak and futile grimdark. I want the agency to impact the world, to do more than choose how the setting grinds my character underfoot.

I’ve played Weirdhope games and they are just as challenging as the bleakest Grimdark RPG. For example, Cloud Empress is Weirdhope, taking inspiration from Nausiccaa. It also uses the Panic Engine from Mothership 1e.

It’s survivors building relationships and community in a post-apocalyptic wasteland. It has rules that encourages exploration and spending down time with new characters. It also has body horror and a magic system that takes an immediate toll on the caster’s body.

Great post!