How I Write Adventures

#017 Thoughts on vision, layout, and creative flow

About 12 years ago, I interned at a small regional newspaper. I remember how, one evening, I was to hand in a short three-column article for the next day’s issue. It came in late and probably wasn’t particularly great. The editor-in-chief was the only person still in office, so it was up to him to proofread my report. He returned it covered in red ink, practically rewritten almost beyond recognition. It felt devastating.

I couldn’t appreciate it at the time, but looking back, I see that he had turned gibberish into something clear, structured, and readable. Writing is a craft.

Since then, writing has remained a core part of my professional life. TTRPG adventures are certainly a genre of its own, though. Right now, I’m working on stretch goals from our recent Kickstarter, and that project has also opened up new opportunities: Golem Productions is entering several collaborations that will lead to future adventures. I’m excited to share more soon.

In the meantime, I thought I’d reflect on the creative process behind writing adventures. Important note: This article isn’t about what makes a great OSR/NSR adventure. For that, for example, you can read

’s post “How To Design Good OSR Adventures”. What I’m sharing here is one writer’s perspective, hopefully a useful complement to the many excellent approaches out there.

Writing: A personal journey

First of all, there is not just one way. In preparation, I’ve read through a few guides on adventure writing to find common cause, but it seems like writing involves some very personal approaches. The OSR/NSR community showcases a spectrum from highly improvisational processes to meticulously planned approaches.

Some writers (sources see below), like Gus L., follow a methodical step-by-step procedure with multiple playtests and revisions. Others, like Ben L., embed the writing process in ongoing play, slowly turning gameplay material into publishable text. Patrick Stuart focuses on nurturing the initial creative spark and then wrestling that big idea into a structured manuscript through sheer iteration. Ron Lundeen outlines adventures with word-count targets and plot beats to hit a deadline.

Yet despite differences, common principles shine through:

Start with inspiration – an idea that excites you and can be expressed as a strong theme or image.

Give your adventure structure – through maps or outlines to organize creativity and ensure a logical flow.

Just write! – get the first draft out without obsessing, using whichever tools or tricks keep you productive. Keep it game-oriented and concise.

Playtest and revise – treat your draft as a hypothesis to be tested at the table. Embrace feedback and iterate to fix issues.

Polish for others – edit ruthlessly for clarity and utility; add art and layout that support ease of use; amplify the cool parts and trim the boring bits.

Learn and evolve – every adventure you write will improve your craft, especially as you reflect on what worked and what didn’t in previous efforts.

Some inspirational sources on the topic:

Gus L. – All Dead Generations, “Most Adventures are Bad – An Adventure Writing Process” (March 26, 2025). Detailed 13-step process for writing and publishing adventures, with emphasis on playtesting and iteration.

Ben L. – Mazirian’s Garden, “My Process” (Oct 2, 2022). (Describes creating adventures out of sandbox campaign prep, with stages from concept to second playthrough to publication.)

Deathtrap Games, “Building an Adventure: Endgame, Style, & Structure” (Oct 5, 2020). Recommends identifying a satisfying climactic encounter and designing backward from it; discusses different adventure types and structures.

Ron Lundeen – Run Amok Blog, “A 5,000-Word Adventure This Weekend” (July 10, 2020). Professional perspective on outlining an adventure with word counts, encounters, and scheduling writing tasks for a quick turnaround.

Skerples – Coins and Scrolls, “Sharpening the Axe – How I Plan and Write RPG Books” (Sept 5, 2019). Loose collection of adventure-writing tips: focus on utility, brevity, and iterative design.

Patrick Stuart – False Machine, “How I Make an Adventure – Part 1” (Jan 2017). Insights on idea generation, using a notepad, breaking into sections, and the emotional journey of writing.

With the myth dispelled, that there is a clear best practice approach to adventure writing, I would like to focus on two aspects that have become particularly clear to me in recent months.

I. Inspiring vision

Perhaps the vaguest and at the same time most important aspect for me: a vision. I know it sounds so simple when you say it like that, but I’m talking about a tangible, inspiring power.

At the beginning of every adventure, I look for a kind of guiding image that I can actually see in my mind’s eye. But it’s not just a colorful motif, it’s a multidimensional mental image that expresses a vibe, an emotion, a concept.

For The Way of the Worm, for example, it was a life-sucking parasite inside a cave on an island that must be discovered and fought. Everything developed from this image. For Ravaged by Storms, it was the storm-controlling Coatl, which dynamically moves from island to island throughout the adventure.

Sometimes the vision contains specific characters or scenes, sometimes even layouts or haptic impressions. This may sound odd, but unlike a mere idea, what I call a vision feels alive, moves independently in my mind, interacts with me, almost as if it were a separate person. This is a deeply creative process. A quest for and a dialogue with the adventure, as if it already existed in its very essence.

As diffuse as my description may sound, I can at least share some advice on how I personally achieve a state that enables a vision:

Give the process clear time and space.

Listen to music that matches the vibe you’re looking for, and dance or take a walk in nature.

Observe. “Watch” the vision instead of actively thinking about it. Try to “experience” it like a movie.

Take short breaks every now and then. Look away and then back again. The vision will continue to develop and become clearer.

What do you do with it?

Once the vision has manifested itself and feels solid, I am ready to write a pitch for my partners and collaborators or a rough summary of the adventure. I can’t seriously work on a text before that.

From there, you can now consciously fuel yourself with further inspiration, for example by reading books or watching films that match the vibe or setting.

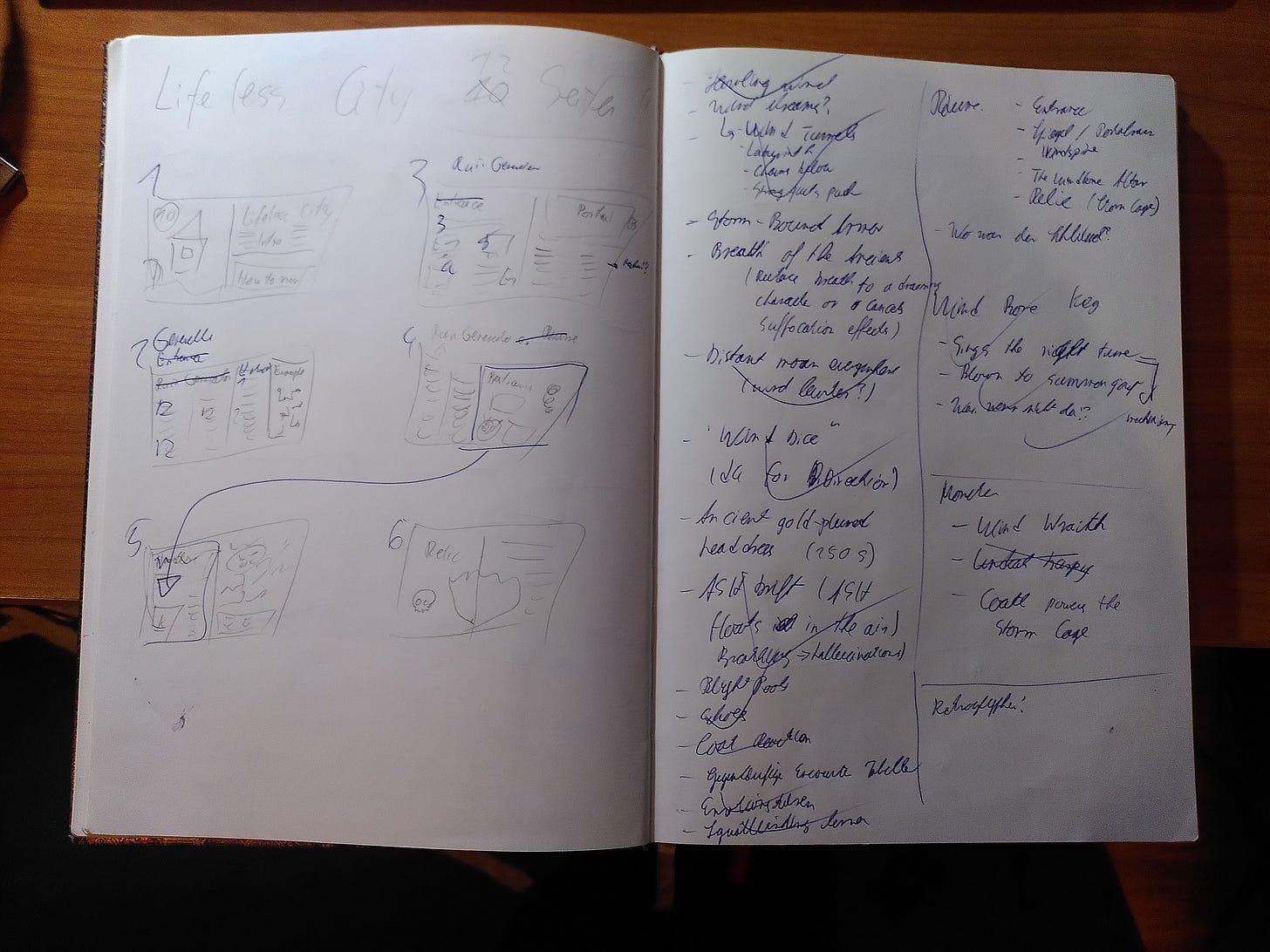

II. Spreads demand planning

I think it’s essential to imagine what the spread might look like in the finished adventure while you’re writing. After all, in addition to clear, melodious words, we ultimately want a product that is easy to understand, evocative, and useful for GMs.

The text needs a clear structure with meaningful hierarchies that are also reflected in the rest of the adventure. Each spread might contain illustrations, tables, or other tools - so space must be left accordingly. How many words can fit on the spread without compromising readability?

In this sense, each spread is a separate unit of meaning. The GM will have them lying open on the table while running certain scenes or when they want to access specific information or tools. Of course, sometimes several spreads belong together, but you still need to think carefully about when and where the break occurs so that the game requires as little page turning or scrolling as possible.

I often read that first of all the text of an adventure is written. Then, iteratively, playtests, revisions, art, and finally the layout follow. With

, I have an art director on the team who is also responsible for our layouts. We both work together on our adventures and complement each other. This allows for an integrated approach.When I write a first draft of a spread, she’ll already put it into a preliminary layout, and it will be clear whether something needs to be shortened or added. Where appropriate, I’ll provide her with scribbles so that she knows how I envisage the spread or a scene, enabling her to create something suitable (or better) and avoiding misunderstandings. Other spreads are designed freely and creatively by her. Sometimes she even creates the artwork for a spread first, and I write the text inspired by it.

This is a special form of collaboration that I really appreciate and that I feel improves the quality of our publications. To make this work, at the beginning of a project like Ravaged by Storms, we discussed our vision and then developed a page plan that outlined the content - both graphic and textual - that a spread would contain and the sequence in which it would appear. However, I would like to highlight two lessons learned:

Admittedly, we often had to adjust the plan during the creative process because the planning turned out to be too rough. It would have been better if we had taken more time for the planning and design phase and made the content per spread more specific, as Luke Gearing describes in his blog post here.

Driven by perfectionism and a desire to offer playtesters the “full” experience, we started our playtests too late, with many spreads already finished. As a result, we were unable to implement all of the valuable insights we gained. Next time, we need to enable playtests with rougher layouts and scribbles.

How I am currently immersing myself in inspiration

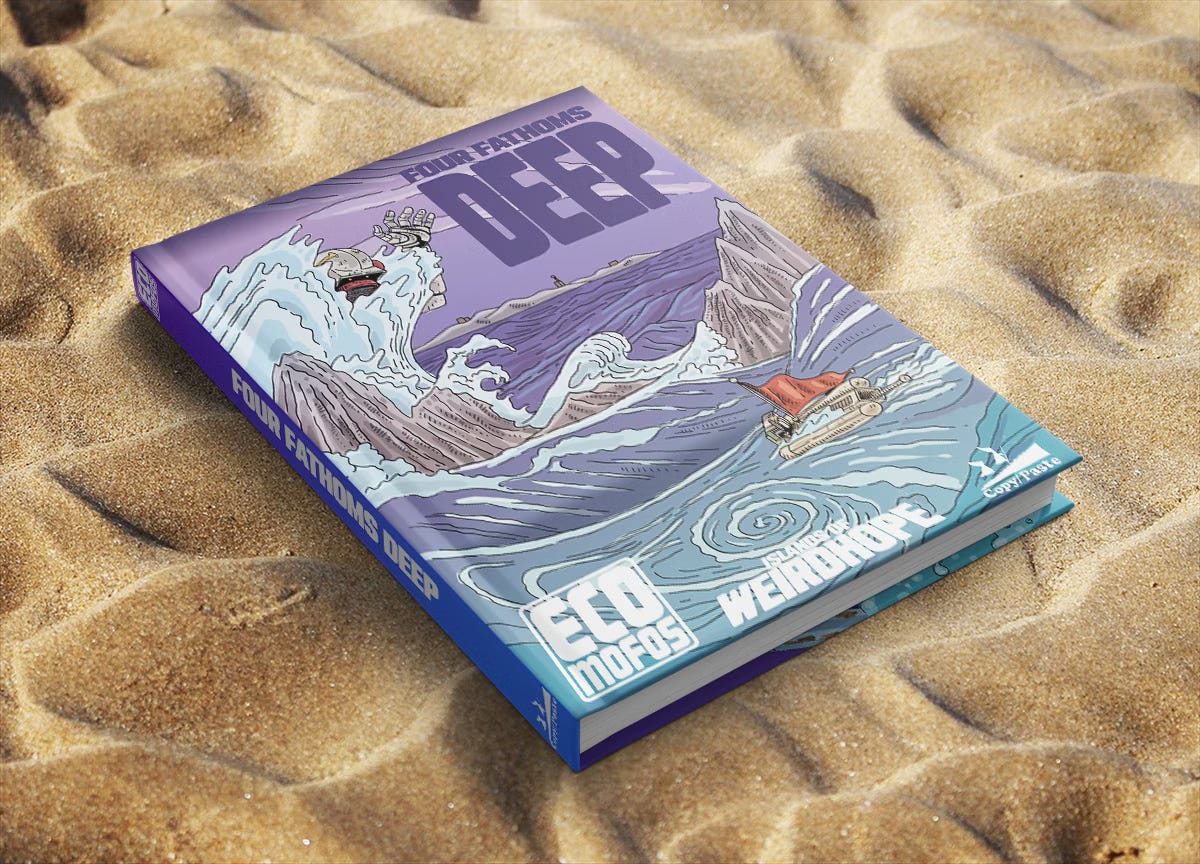

In addition to my work on Pirate Borg-related content, I have recently embarked on a new project. For Four Fathoms Deep (adventure compendium for the Windwaker-meets-Waterworld OSR game Islands of Weirdhope by

), I am currently writing writing Neptun’s Heartstone, an adventure landscape in the floating ruins of a fallen sky fortress, where three factions struggle over a fateful decision about what to do with the fading levitation crystal within the machinery.As described above, I first allowed a vision to emerge. And I refine it through music, films, and thoughtful walks.

What I do, for example:

Reread the Into the Odd core rulebook.

Read and analyze the adventures and core rulebook of the original game ECO MOFOS!!. My two favorites are To Put Away a Sword and The Silo.

Watch a new arc (currently Wa no Kuni) of my favorite anime ONE PIECE.

I’ve been enjoying a lot of nautical adventure stories lately anyway. Pirate History Podcast, anyone!?

Watch Hayao Miyazaki’s classics “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind,” “Laputa: Castle in the Sky,” and maybe “Howl’s Moving Castle.”

How do you get inspired? What are you working on? How do you organize your writing process?

“From pebble to monolith—your journey matters. The Golems have spoken.”

Alexander from Golem Productions

This is a really thoughtful piece. I enjoy seeing how others design their adventures and games.

For me, everything starts with a vibe. Maybe some scenes from a movie or book I enjoy. Then I build out from there. It seems like everything I do involves research to the point of absurdity as well.

My takeaway from this piece is that I need to formulate a document of my process just so that I can stay on track. In most things, I've noticed that having a framework or general roadmap for the process speeds things along a bit and makes the final project better.