Running OSR Dungeons: Turn-by-Turn vs. Narrative Exploration

#011 - How The Hole in the Oak introduced me to turn-based exploration

I still remember the moment when I opened my first real OSR dungeon. I was impressed by the clarity of the layout, the minimalist yet impressive descriptions, and the many possibilities for exploring this place.

I was also a little overwhelmed, having only known more narrative RPGs for more than 15 years. The masterpiece of that time was The Hole in the Oak by Gavin Norman, Necrotic Gnome, now a modern classic. It is the “hole” to which I dedicate today's contribution to

's bandwagon about "holes". Hidden beneath the roots of an oak tree, the hole that gives this adventure its name is the entrance to a wonderfully weird dungeon in the Mythic Underworld, where low-level player characters will encounter numerous strange creatures, monsters, and treasures.More specifically, this post is about the question I asked myself when I first encountered OSR: How am I supposed to run this? Not because anything in the short adventure was unclear, but because I was used to roleplaying a more or less predetermined sequence of scenes, rather than free, narrative exploration.

Want a full review?

In recent years, several excellent reviews and play reports have been written about “The Hole in the Oak,” so I have decided to focus entirely on my question here. If you are not familiar with the adventure, I recommend the reviews by JoeArchitect on reddit and

on YouTube.My disbelief when I realized that OSR was serious about its procedures

Old School Renaissance (OSR, we're not talking about what the "R" can also mean! ;) ) games harken back to early D&D dungeon crawls, where exploration is structured turn-by-turn. In a classic OSR dungeon crawl (e.g. using Old-School Essentials for which The Hole in the Oak was written, a modern B/X clone), an exploration turn traditionally represents 10 minutes of in-game time.

Turn-based exploration is a hallmark of old-school play. “Strict time records” are kept to manage resources and dangers. During each turn, the referee and players go through a set procedure. For example, the Old-School Essentials rules suggest that in one turn the party can cautiously traverse roughly 120 feet of dungeon passage if mapping. After a turn passes, the referee ticks 10 minutes off the clock and may trigger certain checks – resource depletion (torches burning down, etc.) or a wandering monster roll.

This methodical, measured approach to dungeon delving contrasts with more free-form “theater of the mind” exploration, where the GM narrates movement and action without adhering to discrete time chunks or exact distances. This is what I was used to before I found OSR, and frankly, I was quite irritated by the somewhat board game-like approach OSR offered. It felt too structured, too mechanical.

It even got to the point where, at first, I didn't even want to believe that anyone actually followed these procedures. Actual play videos like Questing Beast playing the Dolmenwood adventure Winter's Daughter, also by Gavin Norman, felt bizarre at first, but showed me that it's worth exploring this method of exploration.

The Classic Dungeon Turn Structure in OSR

OSR bloggers like All Dead Generations have documented this exploration turn procedure in detail. In summary, at the start of each turn the referee updates any time-dependent effects and checks for random encounters. Then they describe the immediate surroundings to their players, e.g. what their lantern light reveals down a corridor. The players can ask questions and discuss, then declare their actions for that turn. The referee resolves those actions, and the turn ends with them updating character sheets for any resource usage and rolling the next turn’s random encounter check.

Time, distance, and risk are tightly linked in this old-school structure. By segmenting play into turns, the game makes time a resource that the players must manage. Every turn spent searching a room brings them 10 minutes closer to their supplies running low. It also incurs a chance of a hostile encounter. Taking too long or making too much noise may attract trouble, and believe me The Hole in the Oak can by quite deadly in this regard.

Supply tracking is the other pillar: torches typically last 6 turns (1 hour), so the referee counts down turn by turn until the light goes out. Food, water, and spell durations are handled similarly. In essence, the turn-based crawl turns dungeon exploration into a kind of resource-management mini-game where the party must balance speed vs. caution. They can move faster and cover more ground, but if they rush they risk missing clues or triggering traps; if they move slowly and carefully, they consume time.

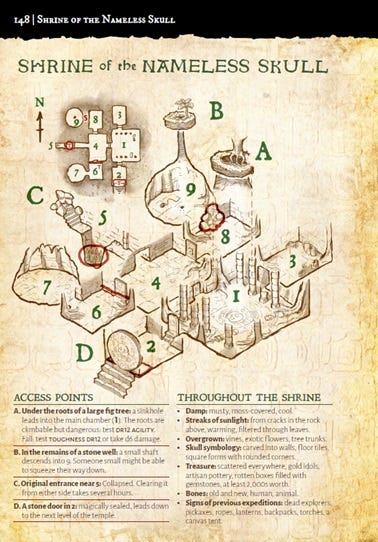

Classic gridded dungeon maps are ideal for this style of play due to their structured nature, especially since traditional OSR games assume that players will draw their own maps as they explore. This is possible thanks to turn-by-turn descriptions of the dungeon and controlled movement. Having players map can facilitate emergent gameplay. By sketching their route, they might spot spatial oddities or plan their moves ahead. This style of play leans into exploration as a challenge: navigating complex loops, corridors, and doors, not just fighting monsters. It’s part of that “exploration” pillar of old-school gaming.

In summary, the classic turn-by-turn crawl is structured but not restrictive. It provides a clear framework for the GM and players to follow, ensuring no one gets lost in the dungeon’s details or pacing, while still allowing all manner of player improvisation within that framework.

Turn-Based vs. Purely Narrative Exploration

Not every group or game uses strict turn procedures for dungeon exploration, though. A common alternative is a more fluid, narrative style, often combined with a play style focused on theater of the mind without any visual aids. With that, the GM might describe the party’s progress in broader strokes rather than counting out every 10-minute increment. For example, a GM might narrate “you carefully make your way down the hallway, probing ahead with a 10-foot pole – after a short while, you arrive at a heavy oak door banded with iron.” Many modern games assume exploration is happening and only call for a random encounter roll or resource deduction at logical intervals. This is in stark contrast to the ethos of explicitly ticking off turns.

A focus on narrative beats rather than simulation has some advantages. I feel it can make the game feel more cinematic and fast-paced, since you’re not stopping every few minutes. If a dungeon is simple or the session time is short, a GM might prefer to summarize exploration instead of playing out each corridor. This approach can work well for one-shots or casual games, where bookkeeping might bog down the fun. It also aligns with groups that prioritize story and role-play over logistical challenges. The GM might handle time and space abstractly, only highlighting interesting moments.

However, going full theater-of-the-mind in old-school dungeons like The Hole in the Oak can have drawbacks, especially for complex environments. Without a map or turn structure, players can become disoriented about the layout. Some referees mitigate this by sketching impromptu maps on a whiteboard or VTT. In effect, they momentarily step back into a tactical mode for clarity.

I assume that many GMs adopt a hybrid, as I often have been doing: they narrate freely but still keep a rough count of time and ask players to keep track of important resources, maintaining some OSR principles without rigidly announcing each turn.

Benefits of Turn-Based Dungeon Exploration

Resource and Tension Management: The foremost benefit is built-in time pressure. By tracking turns, the GM ensures that lantern oil runs dry, and rations get consumed. This creates a constant tension between pushing onward and turning back.

Player Engagement and Caution: Turn structure encourages players to engage with the environment meaningfully. Instead of glossing over exploration, players are prompted every turn to declare actions: “We check the ceiling for slime,” or “We listen at the door before entering.” This fosters a careful, problem-solving mindset.

Fairness and Clarity: The structured approach provides a clear, impartial framework. Because everyone at the table knows how a turn works, it can build player trust. It can also help making running even a large dungeon more manageable.

Emergent Gameplay and Exploration as Challenge: With mapping and turns, exploration becomes a challenge to overcome rather than a trivial segue between combats. Dungeons can have navigation puzzles or hidden clues that only reveal themselves through careful mapping and time investment. Turn-based play supports these elements by making players interact with the dungeon’s geography and timeflow directly.

In short, using exploration turns and maps can transform dungeon delving into a gripping resource management and navigation game within the game. It produces a very different flavor of play – one of suspense, strategy, and slow-burn dread, which is exactly what many OSR gamers love about old-school dungeons.

Drawbacks and Challenges of the Turn-Based Approach

Pacing and Bookkeeping: The most obvious drawback is that meticulous tracking can slow the game down. Stopping every few minutes of real time to ask, “What exactly are each of you doing this turn?” can break immersion if not handled smoothly. There’s also a lot on the referee’s plate – you must keep one eye on the clock (in-game) at all times.

Risk of Rigidity: A related issue is that a strict procedure can become a straitjacket if over-emphasized. If the game devolves into rote turn cycles (“Okay, turn 5: mark off another torch, roll encounters, nothing happens, next…”) it can start feeling like accounting homework rather than adventure. The goal of the game is to have fun, after all.

Learning Curve for New Players: Players new to OSR games might find turn-based dungeon crawling unintuitive or intimidating. Modern 5E doesn’t teach this style. So when players used to “scene-based” play sit down at an OSE table, they might be unsure why the DM is insisting on movement rates and mapping. Some may never warm to it, if they see it as needless complexity. Clear communication is important.

In summary, turn-based exploration requires a bit more work and finesse. It’s a trade-off: you gain depth and tension at the potential cost of speed and simplicity. A successful OSR referee will know when to apply the pressure and when to hand-wave a little for the sake of pacing – e.g. pausing the turn count during an extended roleplay scene or speeding it up during an uneventful stretch.

Modern Variations like in The ALIEN RPG

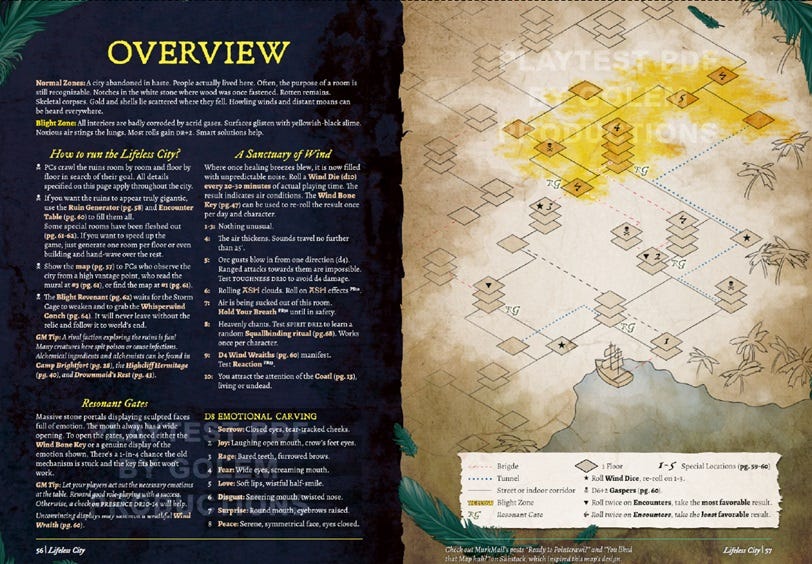

For a modern reference, The ALIEN RPG by Free League Publishing provides a very clear example of adapting dungeon-turn logic to a modern ruleset, that does not identify with OSR. When the game is in Stealth Mode (typically when PCs are sneaking around a xenomorph-infested complex), it explicitly says play is done in turns of about 5–10 minutes of in-game time.

During one such exploration turn, PCs can move through and superficially examine two zones on the map, an abstract unit, which might be one room, corridor, or an area up to ~25 meters across. The GM will describe those zones (what your scanner picks up, any obvious items) but not in detail if you’re just passing through. If the players want to search a zone thoroughly or tinker with something, they have to spend an entire turn in that one zone to do so.

This design is directly analogous to old-school D&D’s approach. The zone-based turn system is a modern reimagining of the dungeon crawl that fits the cinematic style of ALIEN. It's more abstract, but the principle of measured exploration with risks per time unit is the same. It’s interesting as a point of comparison: ALIEN RPG shows you can preserve the function of OSR dungeon turns (resource/encounter cycle) while using newer narrative mechanics.

Closing Thoughts

Ultimately, theater-of-the-mind vs. turn-tracking is a spectrum. OSR purists lean toward the structured end, valuing the procedural game-like nature of dungeon turns. Narrative-focused groups lean toward the free-form end, valuing flow and story. Neither is “right” or “wrong” – they simply create different play experiences. The key is consistency and matching the style to the group’s expectations.

How are you exploring your dungeons?

P.S. Experimenting with new map styles

For our upcoming Pirate Borg adventure Ravaged by Storms we have tried something new: A reinterpreted map style inspired by

's vertical pointcrawl maps that invites free, narrative exploration, while at the same time the adventure offers guidance through less strict procedures and a new Ruin Generator to help fill the dungeon with life. Follow it on Kickstarter!

“From pebble to monolith—your journey matters. The Golems have spoken.”

Alexander from Golem Productions

I'm one of those players used to freeform, narrative dungeon delving who assumed that the procedural mechanics in OSR games were for inspiration moreso than actual implementation. Apologies if that offends any hardcore OSR fans! 😆

However I'm starting a campaign of Eco Mofos which has very procedural overland travel and ruin delving. You've inspired me to engage with the mechanics fully rather than just using them for inspiration.

Eco Mofos is a point crawl, so although there isn't dungeon mapping exactly how you described, it definitely has that risk/reward, push-your-luck element that most OSR games seem to have.

Really useful article! I’ve been discovering this balance between narrative and turn based crawling approaches in my Shadowdark solo campaign. It’s the first time I’ve played in that turn based format and it’s definitely taken a bit of getting used to!