Wandering Monsters Never Sleep

#015 - Wandering monsters set the beat — but your GM instinct makes the music.

As in most years, all my TTRPG groups (there are several …) took their summer break in July/August. They have all resumed playing in September and some of our respective first sessions didn’t go too well. They weren’t bad either but somewhat sluggish, which is not unusual after a long break. And although I was simply exhausted after the successful completion of our Kickstarter earlier this month, I feel that as a GM I could have done better. And that is what this article is about. Pacing.

nailed it in his recent post on pacing being one of the most important GM skills. I’m here waving a lighter in the air because I completely agree. If you keep the game flowing at the right speed, your players will forgive almost anything – a flubbed ruling, a forgotten NPC name, maybe even that time you accidentally TPK’d them with a single goblin (oops). When a session’s pacing is on point, players leave energized. When it’s off, even a richly imagined world can fall flat.

Nate breaks down pacing into three layers (session, scene, campaign) and gives excellent tips: don’t linger on trivial logistics, don’t over-describe the damn doorknob, mix up your highs and lows, take breaks, cut a dull scene early, etc. Yes! Rather than rehash all of his points (go read his post), I want to riff on one specific tool that old-school games use to master pacing: Wandering Monster checks and random encounters. This is my reply to Nate’s post with additional thoughts on how to use encounter tables in OSR games. In some way, this article is also a continuation of the discussion I started in my post Running OSR Dungeons: Turn-by-Turn vs. Narrative Exploration. And it’s a call to us GMs to use these tools with both discipline and artistry.

The OG Pacing Mechanism: Wandering Monsters

In classic D&D (the ur-OSR), the threat of wandering monsters is the drumbeat that keeps the party moving. When players dawdle too long or make too much noise, you roll some dice and – uh oh – something hungry might stumble on them. Old School Essentials (by Gavin Norman, published by Necrotic Gnome) being a tight clone of 1981 Basic D&D, lays this out plainly. When exploring a dungeon, time is tracked in turns (10 minutes in-game). Every turn the referee marks off any resources (torches burning, etc.) and rolls a d6 for a wandering monster; on a 1, something shows up. (Some roll only every other turn for encounters.) If the players are making a racket or moving especially slowly, some refs increase it to 2-in-6.

So, there’s a procedure to be followed, which is transparent enough that a quiet exploration scene becomes tense when everyone knows the clock is ticking on the next encounter roll. Done right, this does two big things for your game’s pacing:

Prevents Analysis Paralysis: If the party spends 30 real-time minutes debating how to cross a pit, by minute 31 a pair of ghouls will creep up and start tearing at their flesh. That will snap them out of debate mode! Wandering encounters are pacing incarnate, the antidote to over-cautious 10-foot-pole creeping. Players learn that dilly-dallying carries consequences, and they’ll start policing their own pace.

Keeps the World Moving: A dungeon isn’t a museum where the heroes are the only thing that matters. It’s a living place. Random encounters – whether it’s monsters, rival adventurers, or environmental hazards – make the world feel alive beyond the PCs’ actions. Players can’t fall asleep because there’s always the sense that anything might happen if time passes. The game moves.

Procedures as pacemakers

Okay, I can practically hear someone saying, “But isn’t following a rigid procedure going to make my game formulaic? I want dynamic and exciting, not some clockwork routine. This is a RPG and not a boardgame, after all.” I’m with you. But here’s the thing: a good procedure creates dynamism; it doesn’t hinder it. It gives you a framework so you’re free to spice it up. Think of it like a solid drumbeat in a rock song – it keeps time, but the guitar and vocals (that’s your story, your players’ shenanigans) riff and soar around it. If the drummer loses the beat, the whole song derails.

A lot of OSR and NSR minds have been chewing on this in recent years, and you’ll find a few blog posts about procedures in RPG design. What all this boils down to is recognizing that RPGs have rules for in-world stuff (combat, spells, exploration, etc.) and rules for the flow of play. Those flow-of-play rules – the procedures – are like your pacing toolkit. Modern games each put their own spin on this, but let’s look at a few more examples to understand the theory.

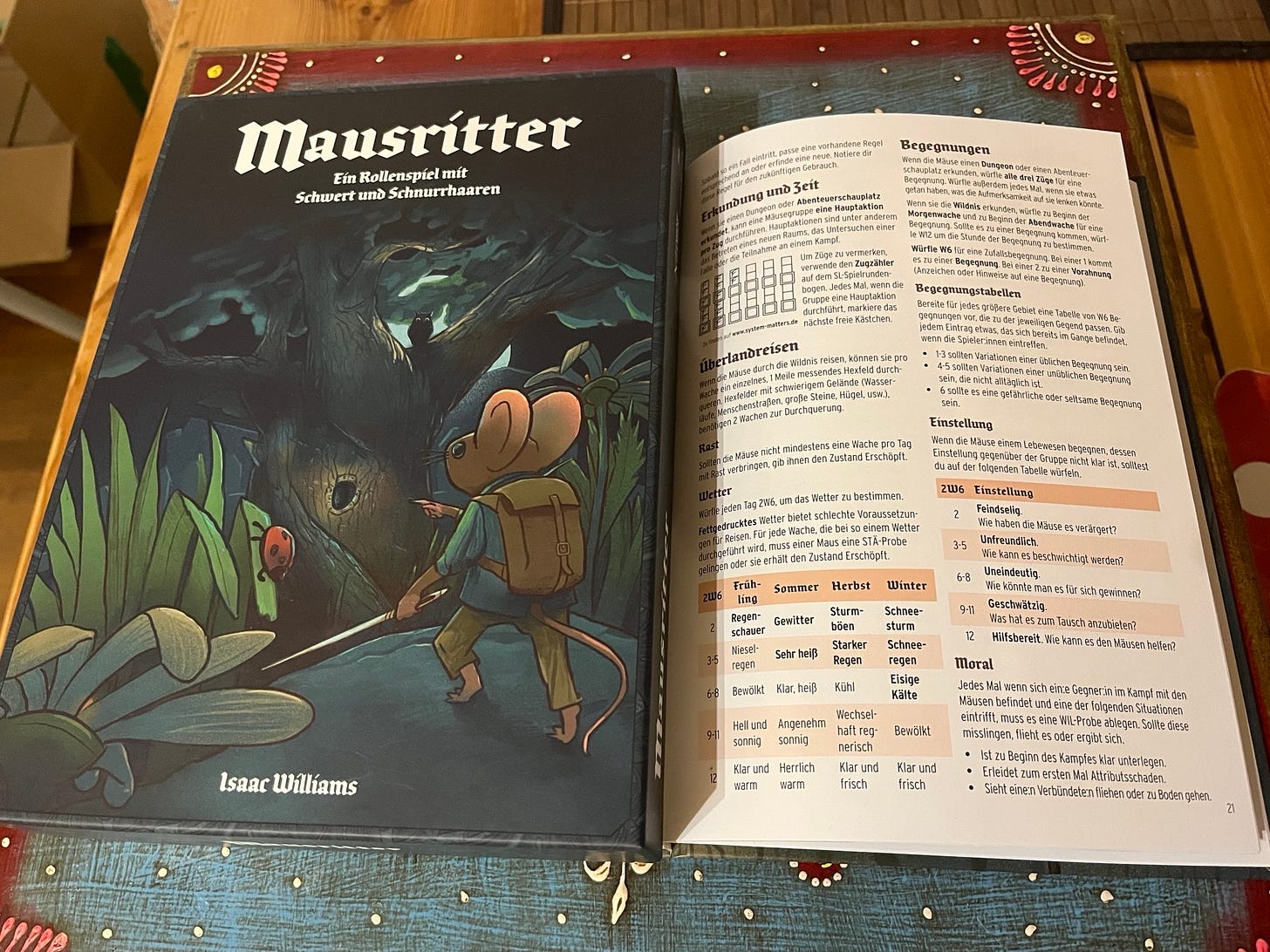

Mausritter (by Isaac Williams, published by Losing Games) adapts classic dungeon-crawl procedures to its small-scale, mouse-hero setting with a clear and simple turn structure. Exploration is measured in turns: as the mice move, search, or fight, the referee marks them off, with light and other resources tracked against that passage of time. In the dungeon, every third turn the referee rolls a d6—on a 1 there’s an encounter, on a 2 an omen of an encounter nearby, otherwise nothing happens.

Some RPGs formalize exploration around the overloaded encounter die (to my knowledge, a concept cribbed from the blog Necropraxis), where a single roll determines not just wandering monsters but also resource attrition, omens, and environmental shifts. His Majesty the Worm (by Josh McCrowell, published by Exalted Funeral) uses an overloaded encounter die in dungeon exploration: a result of 1–2 triggers an encounter, 3–4 causes resource attrition such as light burning low or fatigue, and 5–6 reveals an omen or environmental shift, effectively binding danger, depletion, and pacing into a single die roll.

Mothership (by

, published by Tuesday Knight Games) is a sci-fi horror game where Stress and Panic act as a pacing engine. Every frightening event adds Stress; when it spikes, you roll Panic, and someone might snap spectacularly. Many modules reinforce this with timers and encounter checks—alarms blare, corridors flood, hazards mount. By design, you can’t slow-crawl through a Mothership scenario; if you try, the game’s stress timer will punish you with a crescendo of panic.

When Style Outruns Structure

On the flip side, some modern “OSR-adjacent” games – think the Mörk Borgs and artsy mini-zines – give you flavorful random tables but no guidance on when to use them. I love Borg’s style, but its encounter method is basically: “Here’s a creepy table of 20 terrible things; roll whenever.” That’s fine if you’re an experienced GM with good pacing sense, but easy to misuse if you’re new or tired: roll too little and nothing happens, too often and the players get crushed. I’d rather modules offer at least some guidance on how they’re meant to be run.

Unfortunately, when I was running the session which I described as sluggish at the beginning of this article, I failed to notice when I should have increased the tempo. It’s not the module’s fault, because I was following its clearly outlined procedure. In that specific session, I was too tired to notice I should have either made the encountered faction act on their own more quickly or even added another encounter to mix things up, when my players were discussing for too long. That’s where procedures end and GM instinct begins.

Intuition: Knowing When to Break Your Own Rules

So far I’ve been singing the praises of sticking to a system – keeping that rhythm. Now comes the jazz improv part: sometimes, you gotta break the pattern. The GM’s intuition is still the ultimate judge of pacing. The rulebook isn’t at your table playing with your friends – you are. A solid procedure has your back most of the time, but if following it to the letter would wreck the fun in a particular moment? Ignore it. Great directors sometimes break film editing “rules” for impact, and great GMs sometimes bend or skip a procedure for the good of the session. The trick is knowing when.

For example, let’s say the party just had an exhausting, epic fight and barely survived. They’re licking their wounds and role-playing a heartfelt moment of triumph and relief. The dungeon turn ends… and according to the letter of the rules, it’s time to roll a wandering monster. Do I really want a random wyvern crashing into their camp right this second? Probably not. This is a perfect time to delay or skip the encounter roll. Let them breathe. Hell, let them make camp in peace for once. Your players will never know you quietly fudged a die roll in their favor, and the session’s pacing will be better for it. (If you’re worried about “Emergent narratives!” – that can be a dogma, too.)

Conversely, sometimes the dice don’t give you an encounter when the game actually needs a shake-up. That was true for my session. Maybe the players are hopelessly stuck on a puzzle or doing that over-planning thing. You’ve been dutifully rolling each turn, and nada for a while. This is when I’ll orchestrate a little “noise in the distance” or have an enemy patrol stumble on them even if I didn’t roll a 1. Gasp! Cheating? I prefer to call it proactive pacing. The players won’t care if the monster was per the chart or from behind my screen – they’ll just be reinvigorated that something is happening again. The art here is to not abuse it. Use your power for good: to keep the game fun and dramatic without railroading where the story goes. Don’t use it to constantly ambush the party just because you’re bored or cruel.

Final Thoughts: Keep the Game Moving

To bring it back to Nate’s original point: managing the flow of the game is absolutely a top-tier GM skill. Wandering monsters and encounter procedures are some of the oldest and best tools to do that – they are literally pacing mechanics baked into the game world. Use them! If your game system provides them, try running them as written for a few sessions and notice the difference in tension and player engagement. If your game of choice is scant on procedure, consider borrowing a page from OSE, Mausritter, or your favorite OSR blog’s house rules. And by the way, you don’t have to explain the GM procedures to your players. It might strengthen their immersion, if you don’t!

And then, listen to your game. Watch your players. If they’re on the edge of their seats, don’t you dare pause to consult a table of wandering hamsters. If they’re yawning or stuck, that’s your cue to drop a little chaos in their lap. Pacing isn’t about always going faster; it’s about knowing when to speed up, slow down, or hit the surprise cymbal crash. The classic procedures help you maintain a baseline tempo, and your instincts let you modulate it into a memorable session.

If my September games felt sluggish, it wasn’t for lack of danger – it was because I forgot to keep the beat. So yes – keep an eye on that rhythm of play. Embrace the wandering monster as your pacing pal. After all, an empty dungeon with no surprises is boring – but a dungeon where something could pounce at any time? That’s the stuff of legends, my friends. Keep rocking that OSR vibe and keep the game moving!

What are your pacing techniques? How did you learn to guide the flow of a game session? When did a procedure save you and when was ignoring it the best thing you could have done?

“From pebble to monolith—your journey matters. The Golems have spoken.”

Alexander from Golem Productions

Great article. One thing I’d like to comment on is your example with skipping the encounter roll after a harrowing fight.

Whether it’s a good idea to do so depends on your table’s intended play culture.

In classic/OSR play, story isn’t everything. Player skill expressed via resource management is an important aspect. Skipping that encounter roll means you remove a possible punishment for overextension. If your table is embedded in this play culture, it would remove an important part of satisfaction people derive from the game. Even if there is a wyvern-caused-TPK, it’s a lesson learned for next time.

In story-driven play, or maybe „character-driven” would be more precise (and this means most tables, honestly), you are absolutely right.

When I run a game with a proscribed amount of time like at a con, I normally base pacing on the hour marks. If it's a 3 hour session, I know I want to be done creating characters and entering the world by the end of hour 1, I want to give the players loads of agency and room to explore til the end of hour 2, and by hour 3 I want to have a pretty solid idea of what the climax will be and steer towards that.

I'm not sure how I learned this method, I think it's just what feels right in a con slot to me, and for one shots more generally.

I've been saved by a procedure in Pirate Borg a few times, rolling on the Carousing Table at the top of a session has been great to jump into a one shot. I'm glad I ignored a procedure in Avatar: Legends any time I catch a glance of the combat mechanics. I hope they work at someone's table, but they definitely don't work at mine. I have a hard time seeing the value.